Opinion

Lagbaja : When Generals, the Olúóde, die

By Festus Adedayo

The Yoruba believe in the law of causation, a principle of philosophy which says that, every change in nature is produced by some cause. To buttress this, they posit authoritatively that a tree will never fall in the forest and kill peasants at home. Following this causative trail, they also say that rafters will never sink and kill a passerby (Igi kìí dá l’óko kó pa ará ilé; àjà kìí jìn k’ó pa èrò ònà). Sakara music lord, Yusuff Olatunji, appropriated an ancient Yoruba words of incantation while paying obeisance to the powers and principalities of this world, otherwise called coven initiates, the “àwòròsàsà”. By doing this, he also explored this principle of causation. The rafters can never collapse at the tender feet of a climbing cat – “Àjà kìí jìn m’ólógbò l’ésè, ó d’owó èyin àwòròsàsà,” he sang.

How true for all seasons are these aphorisms? For the recently deceased General Taoreed Abiodun Lagbaja, the trees in the forest of a soldier fell while he was fighting wars in reptiles-laden forest and several deadly operations in creeks. They didn’t kill him. Those same trees, in the form of a mere disease, fell and, like a hawk picks a chicken off existence, he is suddenly killed.

Danish philosopher, poet and social critic, Soren Kierkegaard, reminds us that death is the only finality and certainty. While every other thing about life is finite, with death, it is as sure as the sun will rise. Kierkegaard however said that death is an uncertain certainty because it is not constrained by time nor circumstance. It can strike at any time. Yoruba’s perception of death is not dissimilar to this. They see Death as one insufferable, ugly, wicked and charcoal-dark gnome whose sense of justice is zero. Kierkegaard is almost at one with this ancient Yoruba epistemology of dying and death. He said that, in death, the dead return to dust, to nothingness that they had always been. He proceeds to say that the dead’s efforts to leave any form of immortality of name behind them get frustrated by the hand of time.

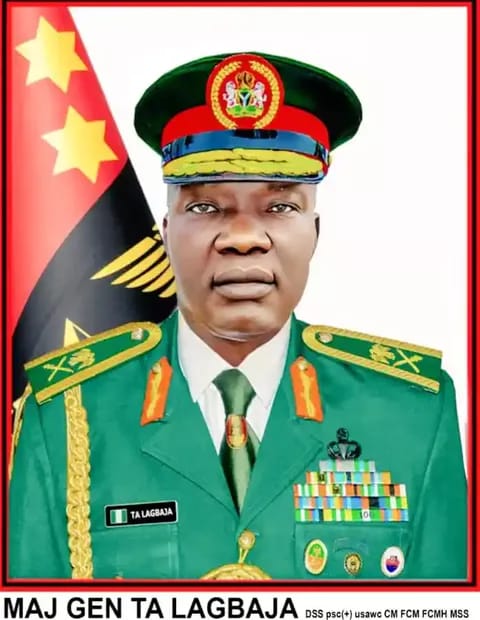

Nigeria’s Chief of Army Staff, General Lagbaja died on November 5 at the age of 56, allegedly from the pangs of cancer. Last Friday, he was given his rites of passage into the bosom of Mother Earth, what humanity profoundly labeled “ashes to ashes, dust to dust.”

In its zero sense of justice, Death offers no explanation for the pain it brings when it perpetually annihilates persons whose births are celebrated. Every hour, humanity loses hundreds of its earthly migrants, reducing them to one unwanted mound flushed six feet beneath earthly surface. The finite nature of man and his perishability were espoused by late reggae musician, Majek Fashek, when he sang “heaven and earth will pass away…but my guitar will never pass away.” If the dead have the power of cognition at their departure, Majek must by now have realized that, against his musical submission of how finite every other thing but his guitar was, the totality of the human race is finite. This includes individuals and cultures which pass away. Everything, including everything about man, eventually passes away. Kiekergard espoused the above in his book entitled At a Graveside’: Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions.

From all the testimonials about him, Lagbaja was apparently a good man. His classmate at St. Charles Grammar School, Osogbo, 1984 set, Bimbo Kolade, in a moving tribute to a man he called by his acronym, TAL, fittingly described his passage as the calamity wreaked on a pod of kolanut by diseases and pests. A kolanut pod can be afflicted by a variety of fungi, one of which is called Penicillium. These fungi cause the nuts to discolor, shrink, or rot. Pests like Kola weevil, moth and worms can also attack kolanuts. When they do, they bore deep into its earthly existence, remove nourishment from it and ultimately take away its masculinity. In his dirge to Lagbaja, Kolade seemed to have gone into the rafters where ancient Yoruba elders keep their possessions and philosophically explained the impact of Lagbaja’s passing. He had written, “Kòkòrò ‘ò jé a gbádùn obì t’ó gbó,” translated to mean, the kola weevil has delinked us from the benefit of chewing a rotund and mature-to-eat kolanut.

Another colleague of his’ in the military, General J.J. Ogunlade (rtd), former General Officer Commanding (GOC) 8 Division Sokoto and Force Commander, Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), in another moving tribute, said “Lagbasky,” the pet name he used to call him, was “one of the most seasoned field commanders in the Nigerian Army,” who he “had the honour of collaborating (with) on numerous operations,” while lauding his “exceptional skills as an infantry soldier and his remarkable prowess as a paratrooper” which “highlight a profound dedication to his responsibilities.”

Professor of anthropology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Eyal Ben-Ari, in his Epilogue to Considering Casualties, a Special Issue of the Armed Forces & Society journal (2005, Vol. 31, No. 4) espoused the theory of “good death” in the military. According to him, “militaries around the world must deal with – handle, manage, or interpret – the casualties perpetrated by them and suffered by their own members.” In other words, the military not only manages violence, injury and demise of its members which include deaths in battles, skirmishes, or engagements, it must also manage the fatalities attracted from traffic accidents, sicknesses, suicide, or training. The military top echelon in virtually all countries prioritizes the welfare, death and remembrance of their compatriots. They get sunk into every aspect of their lives, as well as their deaths. The military, in other words, said Ben-Ari, is responsible for soldiers’ body-building, their bodies-in-use, their body-bags and their “body disposal.”

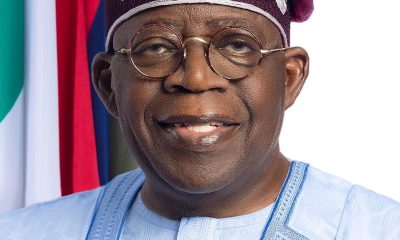

Taking its cue from a hunter’s traditional funeral rites for a departing hunter which the Yoruba call ìsípà ode, the Nigerian military, on Friday, saw off its late Olúóde (Head of hunters), Lieutenant General Lagbaja at the National Cemetery in Abuja. A solemn moment, the ìsípà was attended by top military brass, government officials and members of the diplomatic corps. If you have ever witnessed an Ìrèmòjé – a Yoruba chanting of poetry and rites of passage for a departing hunter – what the military did in Abuja on Friday was a fitting mimicry. Tributes, similar to chants of a deceased hunter’s cognomen and family poetry, marked the rites for Lagbaja with the Olori Olúóde, the Head hunter, or the Ológbojò, head of the masquerades, Nigeria’s Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, President Bola Tinubu, not only attending the burial of his leading war chief, but handing him a posthumous national honour. While conferring the Commander of the Federal Republic (COR) on Lagbaja, Tinubu said it was a mark of appreciation for his invaluable contributions to Nigeria’s security. Chief of Defence Staff, General Christopher Musa, in his tribute, also described Lagbaja’s passing as a call to action for the military.

Perhaps out of esprit de corps, awareness of their own perishability as well or keeping with an ancient tradition they felt they were compelled to honour and reify, traditional Yoruba hunters also keep the memory of a deceased hunter alive. By the way, in traditional Africa, hunters were the soldiers who represented the military command. Warriors like Ogedengbe Agbogungboro of Ijesa land, Basorun Ogunmola and others were hunters and generalissimos. The ìsípà is thus, in a way, a celebration of the god, Ògún. This deity, who became an Alaafin of Oyo, in his early life, was said to have been a hunter. While deifying Ogun, he is memorialized as the controller of all human iron implements which ranged from cutlasses, guns, to swords. Bade Ajuwon, in his “The Preservation of Yoruba Tradition through Hunters’ Funeral Dirges,” published in the Journal of the International African Institute, (Vol. 50, No. 1, 1980), delved into the intricacies of the funeral for the hunter. The Ìrèmòjé, a performance of Yoruba hunters’ funeral dirges, according to him, “is of great human interest because it is an indispensable rite at all the major crises that may affect members of the hunters’ guild.” He said it is evidently a means of emotional outlet for the hunters left behind by the deceased and his family.

Yoruba mythology believes that Iremoje was a coinage by Ifa, who is known as “the god of wisdom and of divination.” Ìrèmòjé is actually a lamentation personally demanded by the Ogun as a performance by his followers “as part of a rite of passage for deceased hunters from earth to heaven.” Ogun was said to have decreed the model of the performance of Ìrèmòjé for the emulation of his followers. Its observance is a ritual used to propitiate their god, a means of communicating with a deceased hunter, and also used to make a thorough appraisal of, in the words of Ajuwon “the successes and failures of deceased hunters in their professional career on earth.” While the Ìrèmòjé is being chanted, a significant historical connection is made with the ancestors of the deceased hunter, emphasizing the hunting victories and heroic deeds of the late hunter. “They praise (the late hunter’s) fine character, his kind heart, his professional skills and techniques, commend his memorable deeds as a hunter, or at least the courage with which he faced ordeals in life,” said Ajuwon. In another journal article, Àjùwòṇ said the Ìsípà Ode rites represent “to the Yoruba hunters a final separation of the deceased hunter from the earthly hunters’ guild. It is the hunters’ belief that once the deceased hunter finally loses his membership in the hunters’ earthly guild, he shall no longer hunt with the living hunters.”

Two Yoruba Ìjálá and Ìrèmòjé chanters who represent the finest art of and who were the most popular ìjálá artists are/were Ògúndáre Fọ́yánmu and Àlàbí Ògúndépò who incidentally hail from Ogbomoso, Oyo State. While Fọ́yánmu’s poetry was a popular brand in the 1970s/80s/90s in Yorubaland, and sold in vinyl, I saw an old but agile Ògúndépò the other day at the burial rites for late ex-Secretary to the Oyo State Government, Adeniyi Koleosho doing what he has almost a global renown for.

The way militaries all over the world deal with the casualties they suffer, the ways in which they deal with their own fatalities are not dissimilar from the way traditional hunters deal with their own dead, too. The question has always been why the military command and the Nigerian state, had to do what they did for Lagbaja on Friday, spending humongous resources and time? Ayo Adeduntan, in his What the forest told me: Yoruba hunter, culture and narrative performance, (2019) citing an earlier Ajuwon submission, gave an explanation. According to him, it was an act of “terminating interaction with the dead.” He justified the Ìsípà ode for hunters thus: “Since all hunters straddle the spiritual and the physical realms… Considering that the hunter’s encounter with spirits, sometimes of the dead, is often anything but friendly, he finds it more agreeable to redefine relations with one’s own dead so that they find their rightful place as ancestors to whom the living hunters must relate as superiors instead of joining the sundry footloose spirits that trouble earthly hunters.”

As myths most times surround passages of the Olúóde, myths also surround the passage of Lagbaja. The late Chief of Army Staff hailed from Ilobu, in Irepodun Local Government of Osun State, a town which straddles two others, Erin Osun and Ifon Orolu who are constantly warring with one another. At his death, some traditionalists and the people of his hometown alleged that Lagbaja’s death was unnatural. The spiritualists also declared that Lagbaja’s spirit could be invoked for vengeance on those connected with his early passing. A traditionalist, Awopegba Ifagbemi pleaded with the Federal Government to release Lagbaja’s corpse to them for a spiritual exercise that would fight his perceived killers. Another said his “killers would not go scot-free.” Lagbaja was said to have begun the building of a hospital for the people of his Ilobu town but the adjoining town claimed the land belonged to it, necessitating the late General building same hospital in the three warring communities. Some people were said to have believed that the people who killed him were the “kòkòrò ‘ò jé a gbádùn obì t’ó gbó”-the kola weevil which transformed into the cancer that allegedly ate up Lagbaja.

Tinubu, the Chief Olúóde’s bestowal of a posthumous COR honour on Lagbaja may also have its roots in the totem of Yorubaland. In very many communities, Yoruba people honour fidelity agreement with even animals. Odidere, the parrot, for instance, is an iconic bird which is a symbol of the city of Iwo due to the significant role it played in the creation of the city. Another case in point is the relationship of the snail to the people of Erin-Oke, located in same Osun State. A mythical accident of history in the 18th century which involved King Akinla Aladekomo was the precursor of the remembrance of this fidelity. Akinla had a ravishingly beautiful wife called Omolere, who one day went to the farm with her maid. On getting to the farm, the Queen reportedly dropped her Iró, the cover-cloth, on a tree while she got embroiled in the task of pruning of weeds. As she did this, small snails which in Yorubaland are called Ìpére, crawled down to the Queen’s clothing and as they crawled, spat their traditional sticky saliva which, when dry, resembles a man’s semen, on it.

When the Queen got home and her husband the king saw the curious hieroglyphics which he took for a sign of sexual intercourse, suspecting adultery, he was furious. Though the Queen pleaded her innocence, the King disclaimed all entreaties and exploding in a fit of anger and impetuosity, ordered that the Queen be beheaded, alongside her maid, who he reasoned must have witnessed the adulterous session but failed to disclose it. Unfortunately, at the death of Queen Omolere, Erin-Oke began to witness the spiritual import of this tragic murder. A string of calamities began to happen in the entire sleepy town which included poor harvests, violent storms, pestilence, epidemics, sudden and premature deaths, among others. The town’s Ifa oracle diviner declared to the king that he was the harbinger of these calamities. As an appeasement of the warring spirit of the beheaded Queen, Ifa recommended deification and eternal remembrance of Queen Omolere. Her effigy was carved and painted in her favourite red colour while small snails, the Ipere, became a taboo for Erin natives which they must never touch nor eat.

Another totem eternally venerated in Yorubaland in the mould of Lagbaja’s COR is the monkey. This is done by the people of Owo in Ondo State. Town remembrancers say that, on their journey from Ile-Ife, the progenitors of Owo people enjoyed a special help from some monkeys who guided them through the forests to their present location. As fidelity with their benefactors, Owo kings, rulers and traditional priests decreed eating of monkeys a taboo among the town’s indigenes, whether they are within or outside the town, wherever they reside.

The death of General Lagbaja, as philosophers say, is a pointer to death as an individual experience. You will die your own death and I will, mine. German philosopher, Martin Heidegger, in his “Being and Time” postulations, has a response to those who lament that Lagbaja died in his plumule, even before he flowered. Heidegger said, “As soon as we are born, we are old enough to die.”

Sleep well, the Olúóde of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.