Special Reports

FOR THE RECORD : MAIDEN CONVOCATION LECTURE OF HALLMARK UNIVERSITY, IJEBU-ITELE, DELIVERED BY PROFESSOR WALE ARE OLAITAN, ON WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 2024

FOR THE RECORD : MAIDEN CONVOCATION LECTURE OF HALLMARK UNIVERSITY, IJEBU-ITELE, DELIVERED BY PROFESSOR WALE ARE OLAITAN, ON WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 2024

Imagining a New Template of Development for Nigeria

Wale Are Olaitan, Professor of Political Science; Former Vice-Chancellor, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago Iwoye, Nigeria;

Chair, Editorial Board, Tribune Newspapers.

Convocation Lecture, Maiden Convocation Ceremonies, Hallmark University, Ijebu-Itele, Nigeria

Opening/Preliminary Remarks

My idea of and take on the assignment I have here today is to have a dialogue – an interactive session – with you graduands and students and Faculty of the University, and, of course, others who are here as Guests for the First Convocation of the University, on my thoughts concerning the future of ourselves and our country on the basis of the deepening state of privation and fitful life and existence being experienced by many, if not most, Nigerians today.

It is, of course, possible for me – since they say and must have stated that I am a teacher and a Professor at that – to come here to give a lecture and expect you all to be here to listen and take copious notes and then depart, perhaps astonished that one man came here and he was so much eloquent about all the big, big and esoteric things he was saying and that he must really be a brilliant teacher of some sort. Only that, to burst your bubble, I am not entirely sure that I see myself in the extremely generous description people have sometimes made of me. Rather I see myself as an ordinary teacher who has been around in the university system and in the world maybe longer than some here and therefore able to allow myself to be invested with the cognomen of Professor – whatever that has come to mean and signify in the deplorable and deteriorating condition of our country, Nigeria, today.

So, I could perhaps get away with having a few people in a class where I could in a way lord myself and whatever I want to say on them under the rubric of being a teacher even as that would not excuse my coming to a large gathering like this and want to pretend that I could impose myself as a teacher on this kind of distinguished audience.

More than that, however, is the realization that we are here talking about addressing new graduands who are set for a new adult life outside of the constrictions of formal institution of learning perhaps for the first time and who are poignantly and studiously ready to unleash their energies and inspirations on the world at this point and going forward. It would rather be much more honourable and dignifying for me – and a ready recognition of the limitations I carry and suffer as part and member of the generation of parents/grandparents of these young ones who have regrettably badly managed our commonwealth as to leave it in its present sorry state for those coming behind – to want to have a dialogue and a productive exchange and interchange with them on the possible course(s) of action that could help provide a leeway out of the current morass in which Nigeria finds itself instead of pretending to have some sort of insights to some enabling platform for the young ones to use to positively transform the country, which insights I and my generation have not provided all these past years.

Dear graduands and distinguished ladies and gentlemen, let me be very clear here – I do not have any great insights to share with you even as I do not intend to bore you with wailing and lamentation about the failure of my generation to do good by the management of the country while we took over and had control.

Trust me when I tell you that we have made such a mess and bad job of running the country to leave the youth today with a prostrate country that is a shadow of all the exciting promises it used to hold for Nigerians and even all blacks in the world.

Some 37 years ago, on Friday, January 30, 1987, when my University, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, had its first Convocation Ceremonies, I was just like you graduates here, also at the threshold of adult life – except that the country we had then gave all of us at that time and point the basis to look forward with optimism. There was no attempt to cook things up while we were undergoing our studies and at the end, we all knew our worth based on our true performances. Those who would be sought after to return to the University as teachers knew themselves and others also acknowledged them based on their performances.

Nobody knew my parents in the University for me to attain whatever record and level I had. Things were done strictly on the basis of merit. I am aware that you would have had something like I had because your University, I am told, has been trying to forge a different name and perspective for itself away from the current general rot in the society. For you ought to know that the privilege you have here of having results consistent with your true performance is not the reality we have in most other universities in the country today because of the prevalence and pervasiveness of corruption and cutting corners. And the rot is not limited to the universities, as the whole country, it could be said, now functions without rules and regulations and there are almost no yardstick for anything to be done than corruption and the ability and capacity to cut corners.

Coming to terms with the current debilitating situation for a new set of graduands would be perplexing, raising multiple questions about what these graduands are expected to do to confront and make a success of life dealing with the negatives of the Nigerian environment. In some other climes with a different university tradition, what we are doing here now is seen as part of Commencement Activities/Ceremonies – providing the opportunity to offer advice and admonition as those who are leaving the university after their studies commence a new, adult life. So what do we expect from these graduands as they set out on a new journey in life – becoming part of the cherished, informed skills available to the country – for the purpose of contributing to their own personal/individual lives and the wellbeing of the communities making up Nigeria? And what could we tell them as they step out into this new life?

We have made allusion to the sorry state of the society and country into which the graduands are stepping at this point. Nigeria, our country, is almost at the rock-bottom of every developmental index and indices, what with the fact that it is spectacularly the new poverty capital of the world – in terms of having the largest number of people who are living below the poverty line, currently denoted by the United Nations (UN) as USD2.15 per day in the world, with 71 million Nigerians officially denoted as living in such defined extreme poverty at the beginning of 2023. (By the way, the World Bank has indicated additional 24 million Nigerians joining the extreme poverty group in the last six months).

The significance of the high number of extremely poor Nigerians comes to the fore when it is realised and recognised that Nigeria’s estimated population of 223 million people only makes it the sixth largest country in the world, meaning that five other countries have larger population including India and China with a population of over 1.4 billion each. And to believe that even countries with such huge population still do not have as many people in extreme poverty as Nigeria, telling about the utter despicable way and manner the country must have been governed and administered over time to signpost 71 million (and now 95 million) of its 223 million population into extreme poverty. Evidently, there must be something wrong with the country or that the country must be doing some things wrongly for it to allow such a huge number of its people under the poverty line. And the frustration with the country would be more when it is realised that even Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) confirms that a total of 133 million Nigerians have been found to be multidimensionally poor – that is to suggest that in addition to having 71 or 95 million of its population in extreme poverty, more than 57 percent of the population as a whole is also multidimensionally poor.

It is not unlikely that Nigeria’s ranking as worst case in open defecation in the world is related to that poverty existence of most of its population, just as it is intriguing that Nigeria is not able to transmit more that 4000 megawatts of electricity for the use of its 223 million population even where the UN prescribes 1000 megawatts for I million people to have reasonable and enough energy for modern undertakings. The UN prescription on electricity remarked here would mean that the country needs a total of 223,000 megawatts and counting for its increasing population, while the reality is that of a country still struggling with 4000 megawatts! This translates to a measly 1.8% of the quantum of electricity we should have given Nigeria’s population. And to believe that the country has been pushing for more electricity generation, transmission and distribution since 1999 under President Olusegun Obasanjo, committing billions of US dollars, even as it is still stuck with the 4000 megawatts transmission 24 years later! We know that Nigeria continues to rank as the largest economy in Africa with a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) put at 477.38 billion US dollar at the end of 2022, but it is the case that we have Egypt and South Africa closely following it with GDP of 475.23 billion and 405.71billion US dollar respectively. But when it is recognized that Egypt has a population of 111 million (less than half of Nigeria’s population and South Africa is only 60 million strong in population (only about a quarter of Nigeria’s population) would it be clear that Nigeria is not very productive compared to those other two countries.

Yet, we know that human existence in the world has to be organised around production for it to be worthwhile and meaningful given that the only way to overcome problems and provide for and satisfy needs is through production. A country or society that is not able to organize production well would be characterized with and be bedeviled by unsolved problems and unmet needs for its people even as it would not be valued or respected by other countries and societies. Witness the fact that South Africa is a foundation member of the group called BRICS, the latest formidable platform for international engagement and pressure in decision-making at that level, while Egypt is one of the six new members proposed for the group even as the application of Nigeria for membership did not sail through.

One way of gauging seriousness is the ability to organise production in order to satisfy needs and solve problems such that nobody takes those with low production seriously, with production also being a reflection of and signposting the capacity to make things happen and get problems solved. Imagine the fact that South Africa is able to generate almost the same level of production with only a quarter of the population of Nigeria – reflecting and speaking to a higher level of organization and functionality and production of and in South Africa.

The unsavoury state of affairs in Nigeria is clear and beyond contention and should present a serious concern to all Nigerians, especially the young ones like our graduands, who have to live life under the context of a non-performing and sub-optimal entity the country has turned into. The troubling situation ought to be a disincentive to the young ones in terms of how to negotiate life within the confounding morass of the Nigerian situation; it must be a challenge to want to go into life and be confronted by a society that is almost completely defined and characterized today by negatives and negativities. Yet, we also know that challenge often comes with opportunities embedded into it.

As it is often said, necessity is the mother and harbinger of invention and innovation. It is precisely because the situation is dire and negative that our graduands would be required to confront it with their sense of ingenuity in order to overcome the negativities all around and chart a new, positive way forward. Sometimes it is the challenge we face that would spur in us the creative juice needed to transcend the problems thrown up. Perhaps in this manner my generation had everything smooth and working well to lull us into the complacency that must have bred and led into the negativities we are all bemoaning today. Conversely, the young ones of today are being called upon and challenged by the extant unsavoury situation to come and work for a turnaround. And fortunately Kailash Satyarthi has said that ‘the power of youth is the common wealth for the entire world. The faces of young people are the faces of our past, our present and our future. No segment in the society can match with the power, idealism, enthusiasm and courage of the young people’, to underline the important contribution the youth could make to positively remaking the future of any society and country. And V. Mani adds :

Youth have historically been at the forefront of social change, driving progress, and challenging the status quo. Their passion, energy, and willingness to question the existing norms make them powerful catalysts for positive transformation in society. … youth bring fresh perspectives to the table. They often question societal norms and push for change in areas such as social justice, environmental protection, and human rights. Their idealism and willingness to challenge entrenched systems are critical for addressing pressing issues.

The country is therefore in a situation in which it could rely on and benefit from the idealism and strength of its youth to confront and seek to change the present for the better, by tapping into the unique opportunity that Nigerian youth have to contribute to helping chart a new, positive course for the country against the background of the pervasive negativity in which the country finds itself today. My brother, Sina Kawonise, in surveying the current trajectory of the country has contended that Nigeria is lucky to have the ‘crowd of the … young turks that are currently leading … (it) in the right direction … (and through them – the youth) Nigeria will rise again … prepared (and preparing) to … (move) to her glorious destiny.’ It would seem like the case for a positive renewal of the debilitating present in Nigeria through the agency and striving and struggle and commitment of the youth is not difficult to make and advance on the strength of their progressive capacities and innate predilection toward change.

The other positive element that could come in handy in the argument we are making for the youth to take the lead in and be at the bedrock of engaging with the present in order to help forge a new positive future is the power of dream and imagination. We, the youth especially, do not have to be overwhelmed by the depth of the negativities defining and surrounding the present environment, but have to see all of it as presaging a better reality that they could work to bring into fruition and reality by working on and from the present. And conceiving of that better future really has to be in terms of dreaming about and imagining it. Says Gloria Steinem, ‘without leaps of imagination, or dreaming, we lose the excitement of possibilities. Dreaming, after all, is a form of planning’, telling us that to dream or to imagine is one of the best way to plan for a better reality and future. And Akira Kurosawa adds that ‘man (and, of course, woman) is a genius when he is dreaming’, to indicate the exceeding power and endowment in dreaming up a better future in order to overcome the obstacles of the present. Indeed, according to Carl Sandburg, ‘nothing happens, unless first we dream’, while Carl Sagan says ‘imagination will often carry us to worlds that never were. But without it we go nowhere.’ What then is this imagination that we are asking our youth to prioritize and make important? Imagination has been said to be ‘the faculty or action of forming new ideas, or images, or concepts of external objects not present to the senses … (or) the ability of the the mind to be creative and resourceful.’ It is about that human capacity to be able to envision a future, an alternative, that is not yet present, that could be brought into being. J.K.Rowling says ‘imagination is … the uniquely human capacity to envision that which is not, and therefore, the foundation of all invention and innovation … its arguably most transformative and revelatory …’ and J.G.Ballard enthuses: ‘I believe in the power of the imagination to remake the world, to release the truth within us, to hold back the night, to transcend …’ while Lloyd Alexander adds: ‘I think imagination is at the heart of everything we do … discoveries couldn’t have happened without imagination ..: Art, music, and … (all) couldn’t exist without imagination.’ Indeed, that preeminent scholar and intellectual, Albert Einstein, is on record as having said that ‘imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.’ Instructively, Einstein did not just leave us with extolling the importance and virtue of imagination, as he also dwelled on the kind of education that could produce and generate that admirable quality in students and learners. For Einstein,

in teaching … there should be extensive discussion of personalities who benefited mankind through independence of character and judgment … (Furthermore) … critical comments by students should be taken in a friendly spirit … accumulation of material should not stifle the student’s independence. … A society’s competitive advantage will come not from how well its schools teach the multiplication and periodic tables, but from how well they stimulate imagination and creativity.

In this kind of education, according to Einstein, ‘more emphasis … (would be) placed on independent thought than on punditry, and young people … (would see) the teacher not as a figure of authority, but, alongside the student, a man of distinct personality.’ Such critical and informed essence of education, Einstein submits, ‘made me clearly realize how much superior an education based on free action and personal responsibility is to one relying on outward authority.’ How critical and important it is for the country to ensure that its system of education is such that could help the students and youth to have not just a creative and resourceful mind, but such that would stimulate their imagination if we are to rely on them to help work out a new and beneficial future for the country! Mercifully and fortunately, I am aware that our graduands here have benefited from such critical and informed education at this University as I remember reading about the extent that the University management and faculty would go to ensure that their students are exposed to and are not deprived of intellectual interaction and engagement with the best in the world in the quest to constantly excite their imagination. In this regard, it is this University that is showing the way to other universities in Nigeria by being the first to have an institutionalized Diaspora Intellectual Remittances Office through which students are helped to benefit from the direct contributions of Nigerian intellectuals scattered all over the world – for Hallmark University, space and location should not be a hindrance to their students having access to teaching by Nigerian intellectuals in other and any parts of the world. Imagine the spectacle ignited in the students in Ijebu-Itele here in rural Nigeria having the experience of direct teaching and intellectual interaction with Nigerian intellectuals in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and such others! We should therefore have no problem tasking our graduands with imagining a new template of development for Nigeria as part of their engaging with the development challenges in Nigeria which they have to confront alongside their other youthful colleagues with a view to contributing to the emergence of a better country. Evidently, to succeed at the task of realizing a better future for themselves, they have to envision and imagine a new, beneficial, functional Nigeria and be prepared to work to bring the envisioned and imagined reality into fruition. It is now to what kind of new template they could imagine for real and workable development in Nigeria that we would turn. Though, first, some clarification on the concepts of production and development.

Of Production and Development

We have already stated that production is at the heart of human existence, both as individuals and as collectives, to the extent that human has needs to satisfy as part of ensuring life and living and there has to be production to make the elements/things (goods and services) to be deployed to satisfy the needs. Production would cover and refer to the processes of goods being made or manufactured, the creation of utility for use in satisfying needs; production takes inputs and uses them to create an output which is fit for consumption – a good or product which has value to an end-user or customer. As John Maynard Keynes puts it, ‘all production is for the purpose of satisfying a consumer’ or need. Yet, it has to be stated that production is not just about getting to work or expending energy on an activity without the end of coming out with something that would satisfy need.

rk and expenditure of energy have to be directed at the goal of creating utility and value of use to give production. The first condition of and for production therefore is the essence of creating value and utility to satisfy need. The next condition would be that the expenditure of energy for the purpose of creating value to satisfy need has to be deliberate; production does not exist as freak or by accident, but through a purposeful and purposive process. Production comes from deliberate work to achieve the end of creating value and this makes the need and requirement for intentionality and conscious willfulness very important. To follow Thomas A. Edison, to have production, ‘there must be forethought, system, planning, intelligence, and honest purpose, as well as perspiration. Seeming to do is not doing.’ It takes a lot of deliberateness and hard work and the infusion of intelligence to have production and the creation of value and utility. And the importance of value and utility resonates in that not all creation would necessarily satisfy value and utility as meeting need is the overriding concern here. If something that is created, even through the deployment of work and expenditure of energy, does not help to satisfy a need, we would not necessarily be in the province of production. Production, as we have earlier stated, happens and operates at both individual and collective level and is at the basis of the healthy functioning of both the individual and the collective. It is at the heart of the capacity of the individual and the collective to satisfy needs. Says Henry George, ‘as it is with an individual, so it is with a nation. One must produce to have, or one will become a have-not’, a poignant argument that helps to explain the root and logical dimension of the crisis of poverty bedevilling Nigeria that we have remarked – the reality that the country is not producing enough to satisfy the needs of its citizens which results in its having so many ‘have nots’ or those in poverty and unable to satisfy basic human and existential needs. It could, therefore, be said that one of the components, if not the real component, of the crises and problems facing Nigeria is that of lack of adequate production even as we know that since production entails deliberateness and infusion of intelligence and planning, there must be more to the lack of adequate production that we are calling attention to here.

There is a logical link between production and development even as they are not the same and one does not necessarily equal the other. Development is often made to refer to and represent the growing capacity of the individual or the collective to satisfy needs, meet challenges and be able to effect a meaningful and worthwhile life and living. At the heart of this conception of development is the capacity – which is said to necessarily be growing if it is to be able to accommodate increasing demands and challenges – to satisfy needs. The capacity referred to could entail many things – thinking, technology, the human factor and such others – necessary to meeting needs. In this regard, it has to be conceded that meeting needs often revolves around providing or producing the items to be used, suggesting production and the capacity for it as the starting point for development. This explains why most iterations of development in the world refer to countries in terms of production as evidenced in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) output, depicting those with high GDP in positive terms. It specifically explains the notion of Nigeria as lacking in development or being in a development conundrum given its low production and GDP vis-a-vis its population and the reality of its inability to provide basic necessities for many of its citizens because of the lack of adequate production. This context justifies the rating of Nigeria as the poverty capital of the world as its inadequate production and capacity could be denoted in terms of the absence of sufficient production with which to provide for the needs and necessities of its people, resulting in Nigeria having more than 71 million citizens, the highest in the world, without the income – USD2.15 – regarded as minimum to help provide basic daily necessities. Development, therefore, entails having the growing production capacity to guarantee enough income for citizens to be able to meet needs, or what Dudley Seers calls having the ‘conditions that lead to a realization of the (minimum) potentials of human personality.’ But we also know that growing production and production capacity, while key and important to any discussion of meeting needs in terms of development in and within a collective, does not necessarily translate into not having citizens without the income to afford them minimum and basic needs given that production outputs have to be distributed at the level of the collective and there is nothing guaranteeing that the distribution of available production proceeds would ensure that none is without income to afford basic needs. This means that, while acknowledging the importance and critical nature of production, it is not enough to guarantee development and the associated and accompanying satisfaction of needs. In this wise, Carter Goodrich has suggested that to ensure satisfaction of needs in a collective and maintain and even increase and raise the standards of such satisfaction, there is the need to ensure that outputs of production and gains from increased production are applied fairly to meet social stability and advance. In which case, the management of the processes of production and the distribution of the proceeds have to be such that helps to effect the satisfaction of needs for the people since the availability of production alone does not guarantee satisfaction of needs. Amartya Sen, the Nobel-winning economist, advances this argument further by showing that the presence and availability of production and accompanying income for people does not necessarily ensure that they would satisfy basic needs as the issue of poverty around non-satisfaction of needs could arise in terms of deprivations in health, education and living standards not captured by income alone. Sen thus introduced the ‘capabilities approach’ through which development is not just about a level of production and income that helps in satisfying basic needs, but includes and entails the capacity and capabilities inherent in maintaining reasonable standards of living for the people. This capabilities’ approach to development finds concretization in the Human Development Index (HDI) through which stock is taken of how individuals fare with regard to provisions for and benefit from health, education, and such other factors as to produce the Multidimensional Poverty Index. Here, rather than concentrating on the income available for each individual to cater to and meet basic human needs under which Nigeria has 71 million of its population below the extreme poverty index, multidimensional poverty index relates to the capacity for reasonable standard of living across, health, education, social standing and such other factors for individuals through which 133 million Nigerians are also found to be below the index of multidimensional existence and development. The reading here means that whereas Nigeria has the problem of low and inadequate production in having a GDP in the same range as 60 million-strong South Africa, its rating at the level of extreme poverty and multidimensional poverty points to problems even with the distribution and allocation of the proceeds of available (low) production, with the stark contradiction of Nigeria having both the richest African and the highest number of poorest Africans! The underlining reality here in Nigeria is that of poverty of production and poverty of distribution and allocation, signifying broad poverty of capability. Incidentally, Amartya Sen has further extended and deepened the conception of development beyond income and capabilities to incorporate freedoms, arguing that the ability of individuals to live a life of freedom, in addition to liveable income and capabilities, ought to be part of consideration in determining the ends of development. Under this deepening extension, Sen submitted that development must be assessed and ‘judged by its impact on people, not only by changes in their income but more generally in terms of their choices, (growing) capabilities and freedoms;’ even as ‘we should be concerned about the distribution of these improvements, not just the simple average for a society.’ Further extension of this conception comes from Owen Barder who posits that the idea of the total wellbeing of people as a fair measure of development is not enough without the provision for such improvements in wellbeing to be sustained. Argues Barder:

rk and expenditure of energy have to be directed at the goal of creating utility and value of use to give production. The first condition of and for production therefore is the essence of creating value and utility to satisfy need. The next condition would be that the expenditure of energy for the purpose of creating value to satisfy need has to be deliberate; production does not exist as freak or by accident, but through a purposeful and purposive process. Production comes from deliberate work to achieve the end of creating value and this makes the need and requirement for intentionality and conscious willfulness very important. To follow Thomas A. Edison, to have production, ‘there must be forethought, system, planning, intelligence, and honest purpose, as well as perspiration. Seeming to do is not doing.’ It takes a lot of deliberateness and hard work and the infusion of intelligence to have production and the creation of value and utility. And the importance of value and utility resonates in that not all creation would necessarily satisfy value and utility as meeting need is the overriding concern here. If something that is created, even through the deployment of work and expenditure of energy, does not help to satisfy a need, we would not necessarily be in the province of production. Production, as we have earlier stated, happens and operates at both individual and collective level and is at the basis of the healthy functioning of both the individual and the collective. It is at the heart of the capacity of the individual and the collective to satisfy needs. Says Henry George, ‘as it is with an individual, so it is with a nation. One must produce to have, or one will become a have-not’, a poignant argument that helps to explain the root and logical dimension of the crisis of poverty bedevilling Nigeria that we have remarked – the reality that the country is not producing enough to satisfy the needs of its citizens which results in its having so many ‘have nots’ or those in poverty and unable to satisfy basic human and existential needs. It could, therefore, be said that one of the components, if not the real component, of the crises and problems facing Nigeria is that of lack of adequate production even as we know that since production entails deliberateness and infusion of intelligence and planning, there must be more to the lack of adequate production that we are calling attention to here.There is a logical link between production and development even as they are not the same and one does not necessarily equal the other. Development is often made to refer to and represent the growing capacity of the individual or the collective to satisfy needs, meet challenges and be able to effect a meaningful and worthwhile life and living. At the heart of this conception of development is the capacity – which is said to necessarily be growing if it is to be able to accommodate increasing demands and challenges – to satisfy needs. The capacity referred to could entail many things – thinking, technology, the human factor and such others – necessary to meeting needs. In this regard, it has to be conceded that meeting needs often revolves around providing or producing the items to be used, suggesting production and the capacity for it as the starting point for development. This explains why most iterations of development in the world refer to countries in terms of production as evidenced in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) output, depicting those with high GDP in positive terms. It specifically explains the notion of Nigeria as lacking in development or being in a development conundrum given its low production and GDP vis-a-vis its population and the reality of its inability to provide basic necessities for many of its citizens because of the lack of adequate production. This context justifies the rating of Nigeria as the poverty capital of the world as its inadequate production and capacity could be denoted in terms of the absence of sufficient production with which to provide for the needs and necessities of its people, resulting in Nigeria having more than 71 million citizens, the highest in the world, without the income – USD2.15 – regarded as minimum to help provide basic daily necessities. Development, therefore, entails having the growing production capacity to guarantee enough income for citizens to be able to meet needs, or what Dudley Seers calls having the ‘conditions that lead to a realization of the (minimum) potentials of human personality.’ But we also know that growing production and production capacity, while key and important to any discussion of meeting needs in terms of development in and within a collective, does not necessarily translate into not having citizens without the income to afford them minimum and basic needs given that production outputs have to be distributed at the level of the collective and there is nothing guaranteeing that the distribution of available production proceeds would ensure that none is without income to afford basic needs. This means that, while acknowledging the importance and critical nature of production, it is not enough to guarantee development and the associated and accompanying satisfaction of needs. In this wise, Carter Goodrich has suggested that to ensure satisfaction of needs in a collective and maintain and even increase and raise the standards of such satisfaction, there is the need to ensure that outputs of production and gains from increased production are applied fairly to meet social stability and advance. In which case, the management of the processes of production and the distribution of the proceeds have to be such that helps to effect the satisfaction of needs for the people since the availability of production alone does not guarantee satisfaction of needs. Amartya Sen, the Nobel-winning economist, advances this argument further by showing that the presence and availability of production and accompanying income for people does not necessarily ensure that they would satisfy basic needs as the issue of poverty around non-satisfaction of needs could arise in terms of deprivations in health, education and living standards not captured by income alone. Sen thus introduced the ‘capabilities approach’ through which development is not just about a level of production and income that helps in satisfying basic needs, but includes and entails the capacity and capabilities inherent in maintaining reasonable standards of living for the people. This capabilities’ approach to development finds concretization in the Human Development Index (HDI) through which stock is taken of how individuals fare with regard to provisions for and benefit from health, education, and such other factors as to produce the Multidimensional Poverty Index. Here, rather than concentrating on the income available for each individual to cater to and meet basic human needs under which Nigeria has 71 million of its population below the extreme poverty index, multidimensional poverty index relates to the capacity for reasonable standard of living across, health, education, social standing and such other factors for individuals through which 133 million Nigerians are also found to be below the index of multidimensional existence and development. The reading here means that whereas Nigeria has the problem of low and inadequate production in having a GDP in the same range as 60 million-strong South Africa, its rating at the level of extreme poverty and multidimensional poverty points to problems even with the distribution and allocation of the proceeds of available (low) production, with the stark contradiction of Nigeria having both the richest African and the highest number of poorest Africans! The underlining reality here in Nigeria is that of poverty of production and poverty of distribution and allocation, signifying broad poverty of capability. Incidentally, Amartya Sen has further extended and deepened the conception of development beyond income and capabilities to incorporate freedoms, arguing that the ability of individuals to live a life of freedom, in addition to liveable income and capabilities, ought to be part of consideration in determining the ends of development. Under this deepening extension, Sen submitted that development must be assessed and ‘judged by its impact on people, not only by changes in their income but more generally in terms of their choices, (growing) capabilities and freedoms;’ even as ‘we should be concerned about the distribution of these improvements, not just the simple average for a society.’ Further extension of this conception comes from Owen Barder who posits that the idea of the total wellbeing of people as a fair measure of development is not enough without the provision for such improvements in wellbeing to be sustained. Argues Barder:

rk and expenditure of energy have to be directed at the goal of creating utility and value of use to give production. The first condition of and for production therefore is the essence of creating value and utility to satisfy need. The next condition would be that the expenditure of energy for the purpose of creating value to satisfy need has to be deliberate; production does not exist as freak or by accident, but through a purposeful and purposive process. Production comes from deliberate work to achieve the end of creating value and this makes the need and requirement for intentionality and conscious willfulness very important. To follow Thomas A. Edison, to have production, ‘there must be forethought, system, planning, intelligence, and honest purpose, as well as perspiration. Seeming to do is not doing.’ It takes a lot of deliberateness and hard work and the infusion of intelligence to have production and the creation of value and utility. And the importance of value and utility resonates in that not all creation would necessarily satisfy value and utility as meeting need is the overriding concern here. If something that is created, even through the deployment of work and expenditure of energy, does not help to satisfy a need, we would not necessarily be in the province of production. Production, as we have earlier stated, happens and operates at both individual and collective level and is at the basis of the healthy functioning of both the individual and the collective. It is at the heart of the capacity of the individual and the collective to satisfy needs. Says Henry George, ‘as it is with an individual, so it is with a nation. One must produce to have, or one will become a have-not’, a poignant argument that helps to explain the root and logical dimension of the crisis of poverty bedevilling Nigeria that we have remarked – the reality that the country is not producing enough to satisfy the needs of its citizens which results in its having so many ‘have nots’ or those in poverty and unable to satisfy basic human and existential needs. It could, therefore, be said that one of the components, if not the real component, of the crises and problems facing Nigeria is that of lack of adequate production even as we know that since production entails deliberateness and infusion of intelligence and planning, there must be more to the lack of adequate production that we are calling attention to here.There is a logical link between production and development even as they are not the same and one does not necessarily equal the other. Development is often made to refer to and represent the growing capacity of the individual or the collective to satisfy needs, meet challenges and be able to effect a meaningful and worthwhile life and living. At the heart of this conception of development is the capacity – which is said to necessarily be growing if it is to be able to accommodate increasing demands and challenges – to satisfy needs. The capacity referred to could entail many things – thinking, technology, the human factor and such others – necessary to meeting needs. In this regard, it has to be conceded that meeting needs often revolves around providing or producing the items to be used, suggesting production and the capacity for it as the starting point for development. This explains why most iterations of development in the world refer to countries in terms of production as evidenced in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) output, depicting those with high GDP in positive terms. It specifically explains the notion of Nigeria as lacking in development or being in a development conundrum given its low production and GDP vis-a-vis its population and the reality of its inability to provide basic necessities for many of its citizens because of the lack of adequate production. This context justifies the rating of Nigeria as the poverty capital of the world as its inadequate production and capacity could be denoted in terms of the absence of sufficient production with which to provide for the needs and necessities of its people, resulting in Nigeria having more than 71 million citizens, the highest in the world, without the income – USD2.15 – regarded as minimum to help provide basic daily necessities. Development, therefore, entails having the growing production capacity to guarantee enough income for citizens to be able to meet needs, or what Dudley Seers calls having the ‘conditions that lead to a realization of the (minimum) potentials of human personality.’ But we also know that growing production and production capacity, while key and important to any discussion of meeting needs in terms of development in and within a collective, does not necessarily translate into not having citizens without the income to afford them minimum and basic needs given that production outputs have to be distributed at the level of the collective and there is nothing guaranteeing that the distribution of available production proceeds would ensure that none is without income to afford basic needs. This means that, while acknowledging the importance and critical nature of production, it is not enough to guarantee development and the associated and accompanying satisfaction of needs. In this wise, Carter Goodrich has suggested that to ensure satisfaction of needs in a collective and maintain and even increase and raise the standards of such satisfaction, there is the need to ensure that outputs of production and gains from increased production are applied fairly to meet social stability and advance. In which case, the management of the processes of production and the distribution of the proceeds have to be such that helps to effect the satisfaction of needs for the people since the availability of production alone does not guarantee satisfaction of needs. Amartya Sen, the Nobel-winning economist, advances this argument further by showing that the presence and availability of production and accompanying income for people does not necessarily ensure that they would satisfy basic needs as the issue of poverty around non-satisfaction of needs could arise in terms of deprivations in health, education and living standards not captured by income alone. Sen thus introduced the ‘capabilities approach’ through which development is not just about a level of production and income that helps in satisfying basic needs, but includes and entails the capacity and capabilities inherent in maintaining reasonable standards of living for the people. This capabilities’ approach to development finds concretization in the Human Development Index (HDI) through which stock is taken of how individuals fare with regard to provisions for and benefit from health, education, and such other factors as to produce the Multidimensional Poverty Index. Here, rather than concentrating on the income available for each individual to cater to and meet basic human needs under which Nigeria has 71 million of its population below the extreme poverty index, multidimensional poverty index relates to the capacity for reasonable standard of living across, health, education, social standing and such other factors for individuals through which 133 million Nigerians are also found to be below the index of multidimensional existence and development. The reading here means that whereas Nigeria has the problem of low and inadequate production in having a GDP in the same range as 60 million-strong South Africa, its rating at the level of extreme poverty and multidimensional poverty points to problems even with the distribution and allocation of the proceeds of available (low) production, with the stark contradiction of Nigeria having both the richest African and the highest number of poorest Africans! The underlining reality here in Nigeria is that of poverty of production and poverty of distribution and allocation, signifying broad poverty of capability. Incidentally, Amartya Sen has further extended and deepened the conception of development beyond income and capabilities to incorporate freedoms, arguing that the ability of individuals to live a life of freedom, in addition to liveable income and capabilities, ought to be part of consideration in determining the ends of development. Under this deepening extension, Sen submitted that development must be assessed and ‘judged by its impact on people, not only by changes in their income but more generally in terms of their choices, (growing) capabilities and freedoms;’ even as ‘we should be concerned about the distribution of these improvements, not just the simple average for a society.’ Further extension of this conception comes from Owen Barder who posits that the idea of the total wellbeing of people as a fair measure of development is not enough without the provision for such improvements in wellbeing to be sustained. Argues Barder:

Work and expenditure of energy have to be directed at the goal of creating utility and value of use to give production. The first condition of and for production therefore is the essence of creating value and utility to satisfy need. The next condition would be that the expenditure of energy for the purpose of creating value to satisfy need has to be deliberate; production does not exist as freak or by accident, but through a purposeful and purposive process. Production comes from deliberate work to achieve the end of creating value and this makes the need and requirement for intentionality and conscious willfulness very important. To follow Thomas A. Edison, to have production, ‘there must be forethought, system, planning, intelligence, and honest purpose, as well as perspiration. Seeming to do is not doing.’ It takes a lot of deliberateness and hard work and the infusion of intelligence to have production and the creation of value and utility. And the importance of value and utility resonates in that not all creation would necessarily satisfy value and utility as meeting need is the overriding concern here. If something that is created, even through the deployment of work and expenditure of energy, does not help to satisfy a need, we would not necessarily be in the province of production. Production, as we have earlier stated, happens and operates at both individual and collective level and is at the basis of the healthy functioning of both the individual and the collective. It is at the heart of the capacity of the individual and the collective to satisfy needs. Says Henry George, ‘as it is with an individual, so it is with a nation. One must produce to have, or one will become a have-not’, a poignant argument that helps to explain the root and logical dimension of the crisis of poverty bedevilling Nigeria that we have remarked – the reality that the country is not producing enough to satisfy the needs of its citizens which results in its having so many ‘have nots’ or those in poverty and unable to satisfy basic human and existential needs. It could, therefore, be said that one of the components, if not the real component, of the crises and problems facing Nigeria is that of lack of adequate production even as we know that since production entails deliberateness and infusion of intelligence and planning, there must be more to the lack of adequate production that we are calling attention to here.There is a logical link between production and development even as they are not the same and one does not necessarily equal the other. Development is often made to refer to and represent the growing capacity of the individual or the collective to satisfy needs, meet challenges and be able to effect a meaningful and worthwhile life and living. At the heart of this conception of development is the capacity – which is said to necessarily be growing if it is to be able to accommodate increasing demands and challenges – to satisfy needs. The capacity referred to could entail many things – thinking, technology, the human factor and such others – necessary to meeting needs. In this regard, it has to be conceded that meeting needs often revolves around providing or producing the items to be used, suggesting production and the capacity for it as the starting point for development. This explains why most iterations of development in the world refer to countries in terms of production as evidenced in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) output, depicting those with high GDP in positive terms. It specifically explains the notion of Nigeria as lacking in development or being in a development conundrum given its low production and GDP vis-a-vis its population and the reality of its inability to provide basic necessities for many of its citizens because of the lack of adequate production. This context justifies the rating of Nigeria as the poverty capital of the world as its inadequate production and capacity could be denoted in terms of the absence of sufficient production with which to provide for the needs and necessities of its people, resulting in Nigeria having more than 71 million citizens, the highest in the world, without the income – USD2.15 – regarded as minimum to help provide basic daily necessities. Development, therefore, entails having the growing production capacity to guarantee enough income for citizens to be able to meet needs, or what Dudley Seers calls having the ‘conditions that lead to a realization of the (minimum) potentials of human personality.’ But we also know that growing production and production capacity, while key and important to any discussion of meeting needs in terms of development in and within a collective, does not necessarily translate into not having citizens without the income to afford them minimum and basic needs given that production outputs have to be distributed at the level of the collective and there is nothing guaranteeing that the distribution of available production proceeds would ensure that none is without income to afford basic needs. This means that, while acknowledging the importance and critical nature of production, it is not enough to guarantee development and the associated and accompanying satisfaction of needs. In this wise, Carter Goodrich has suggested that to ensure satisfaction of needs in a collective and maintain and even increase and raise the standards of such satisfaction, there is the need to ensure that outputs of production and gains from increased production are applied fairly to meet social stability and advance. In which case, the management of the processes of production and the distribution of the proceeds have to be such that helps to effect the satisfaction of needs for the people since the availability of production alone does not guarantee satisfaction of needs. Amartya Sen, the Nobel-winning economist, advances this argument further by showing that the presence and availability of production and accompanying income for people does not necessarily ensure that they would satisfy basic needs as the issue of poverty around non-satisfaction of needs could arise in terms of deprivations in health, education and living standards not captured by income alone. Sen thus introduced the ‘capabilities approach’ through which development is not just about a level of production and income that helps in satisfying basic needs, but includes and entails the capacity and capabilities inherent in maintaining reasonable standards of living for the people. This capabilities’ approach to development finds concretization in the Human Development Index (HDI) through which stock is taken of how individuals fare with regard to provisions for and benefit from health, education, and such other factors as to produce the Multidimensional Poverty Index. Here, rather than concentrating on the income available for each individual to cater to and meet basic human needs under which Nigeria has 71 million of its population below the extreme poverty index, multidimensional poverty index relates to the capacity for reasonable standard of living across, health, education, social standing and such other factors for individuals through which 133 million Nigerians are also found to be below the index of multidimensional existence and development. The reading here means that whereas Nigeria has the problem of low and inadequate production in having a GDP in the same range as 60 million-strong South Africa, its rating at the level of extreme poverty and multidimensional poverty points to problems even with the distribution and allocation of the proceeds of available (low) production, with the stark contradiction of Nigeria having both the richest African and the highest number of poorest Africans! The underlining reality here in Nigeria is that of poverty of production and poverty of distribution and allocation, signifying broad poverty of capability. Incidentally, Amartya Sen has further extended and deepened the conception of development beyond income and capabilities to incorporate freedoms, arguing that the ability of individuals to live a life of freedom, in addition to liveable income and capabilities, ought to be part of consideration in determining the ends of development. Under this deepening extension, Sen submitted that development must be assessed and ‘judged by its impact on people, not only by changes in their income but more generally in terms of their choices, (growing) capabilities and freedoms;’ even as ‘we should be concerned about the distribution of these improvements, not just the simple average for a society.’ Further extension of this conception comes from Owen Barder who posits that the idea of the total wellbeing of people as a fair measure of development is not enough without the provision for such improvements in wellbeing to be sustained. Argues Barder:

to define development as an improvement in people’s well-being does not do justice to what the term means … Development also carries a connotation of lasting change. Providing a person with a bednet or a water pump can often be an excellent, cost-effective way to improve her well-being, but if the improvement goes away when we stop providing the bednet or pump, we would not normally describe that as development. This suggests that development consists of more than improvements in the well-being of citizens (at a single point), even broadly defined: it also conveys something about the capacity of economic, political and social systems to provide the circumstances for that well-being on a sustainable, long-term basis.

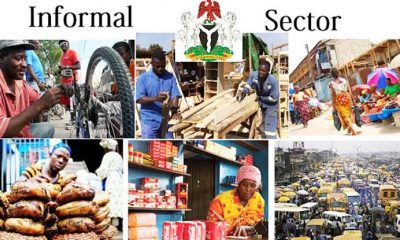

In which case, we must look beyond the provision for the wellbeing of people at a specific point and be more concerned with the capacity of the system to provide the circumstances for continued and sustained and sustainable well-being. Development becomes a characteristic of the system in terms of how it works to provide reasonable and sustainable wellbeing for the people, with ‘sustained improvements in individual well-being … (as) a yardstick by which it is judged.’Development, therefore, comes out as based on and issuing out of production, but still covering the distribution and allocation of the proceeds of production to help satisfy needs of the members of the society in such a way that would assure every member of reasonable standard of life and living including the sense of freedom and humanity for them in a sustained and sustainable manner. The sustained and sustainable provision and assurance of the general and comprehensive wellbeing of citizens and members of the society becomes the defining essence of development in this regard. The outgrowth of this position is that where there is not enough production to meet basic needs of the people and where some live below reasonable standard of living and are not able to afford and guarantee a sense of worthy existence and life for some inhabitants, such a society or societies would be termed as lacking in development and enmeshed in a development conundrum, which is the unfortunate position and situation of Nigeria today. Our concern therefore should be since we know what development connotes and also understand its absence in Nigeria at the moment, what could be done to engineer and work for real development in the country and how do we go about doing this in terms of the template and framework to follow.